Hi and welcome to an ongoing series of blog posts on our current job restoring windows of the historic Haller house, located right in the middle of the small town of Coupeville, Wa on Whidbey island. Located approximately 71 miles from our business location, Coupeville is known for its wonderful seafood (mussels, specifically) and charming old-timey main street lined with mostly original buildings, which now contain cute local shops. With the assistance of a state grant, the Haller House is undergoing a complete restoration and we are very excited to be a part of this project! Throughout this job I will try to regularly post before and after pictures of shop and onsite work.

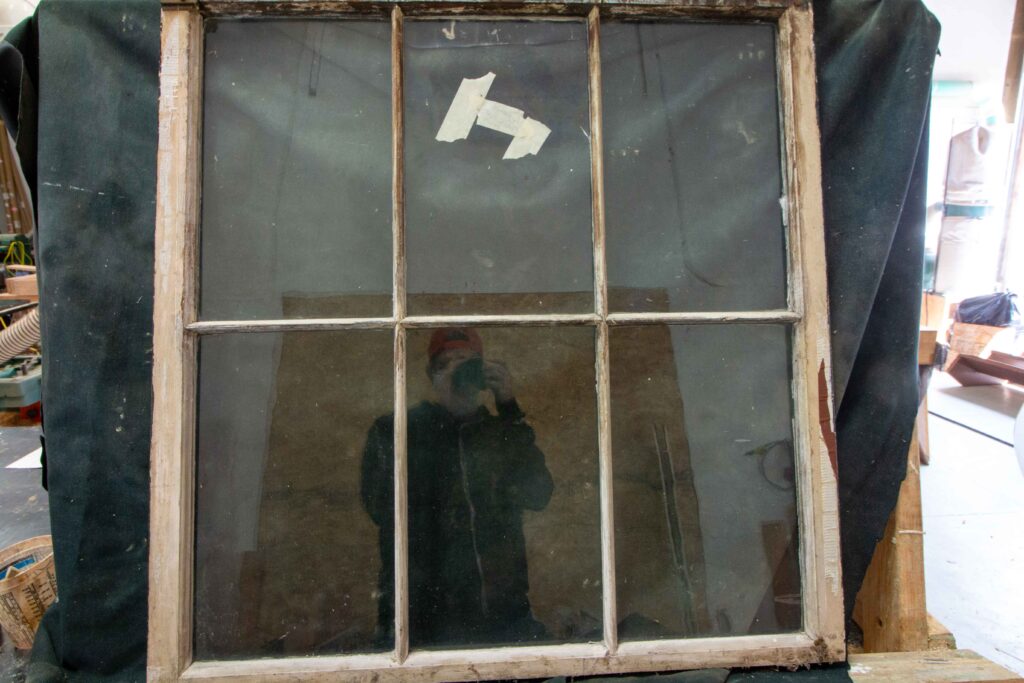

Below is a documentation of the first windows we pulled. These are photos taken in our shop before any work has been performed on the sash to show their condition and work done previously from other people.